MAYFLOWER

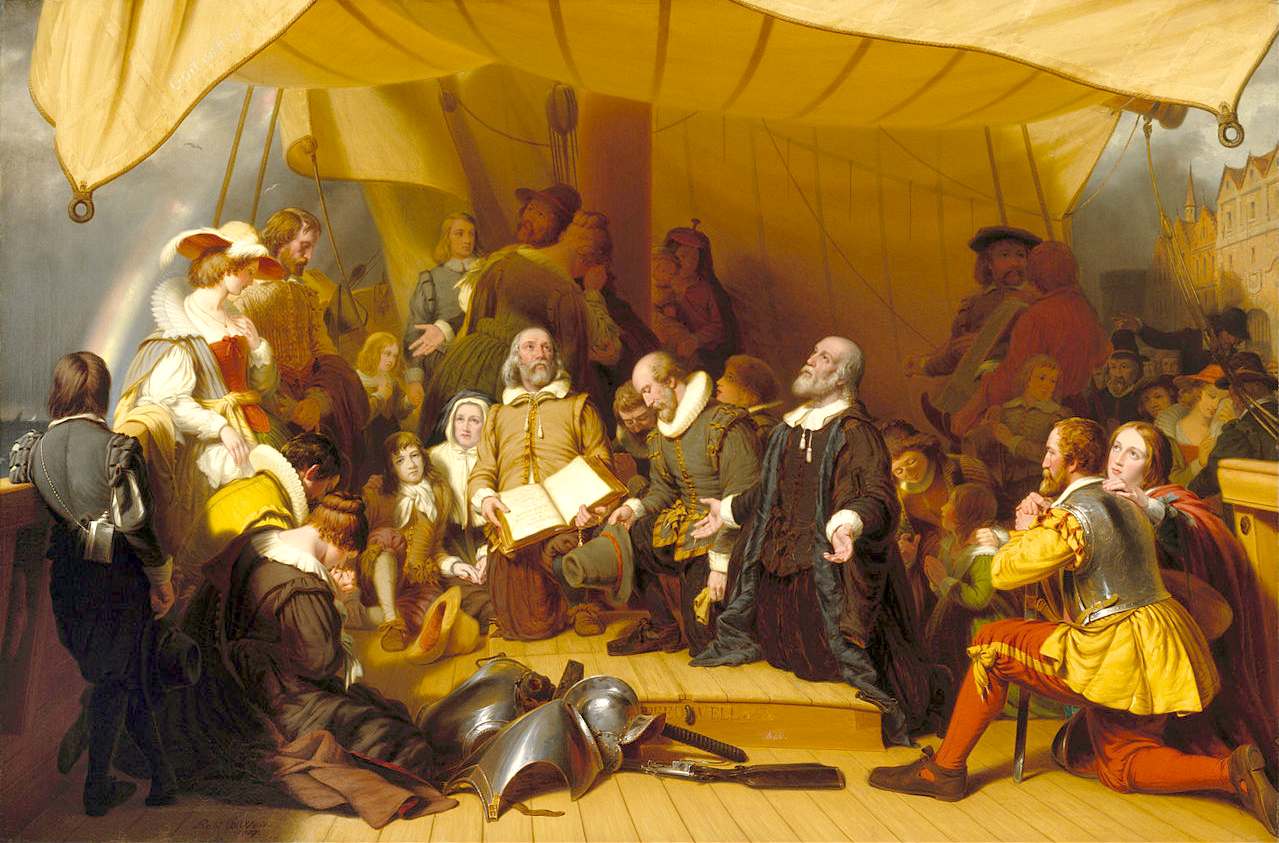

- Loading of the famous ship that was too small to be noted at the Port

of Plymouth in 1620, but went on to become one of the best known sailing

vessels, the world over. The failure to log this vessel can be explained

by the fact that the Pilgrims had already been captured several times

trying to flee England in other ships. It follows that they would not

have been keen to have the vessel noted, and probably paid to keep it

that way.

The original 30-meter Mayflower took 66 days to carry pilgrims from

Devon in the U.K. to what is now the Massachusetts in the U.S.

MAYFLOWER CHARTER - COMPACT

The charter was incomplete for the Plymouth Council for New England when the colonists departed England (it was granted while they were in transit on November 3/13). They arrived without a patent; the older Wincob patent was from their abandoned dealings with the London Company. Some of the passengers, aware of the situation, suggested that they were free to do as they chose upon landing, without a patent in place, and to ignore the contract with the investors.

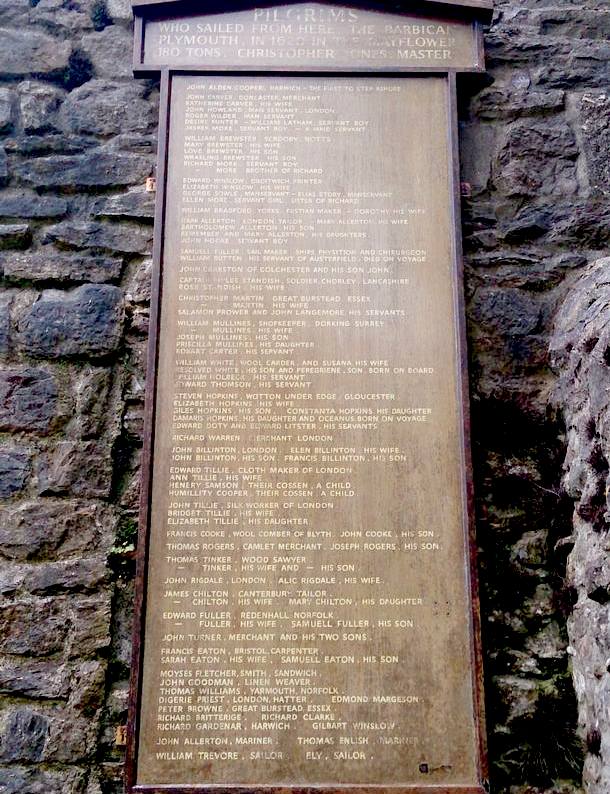

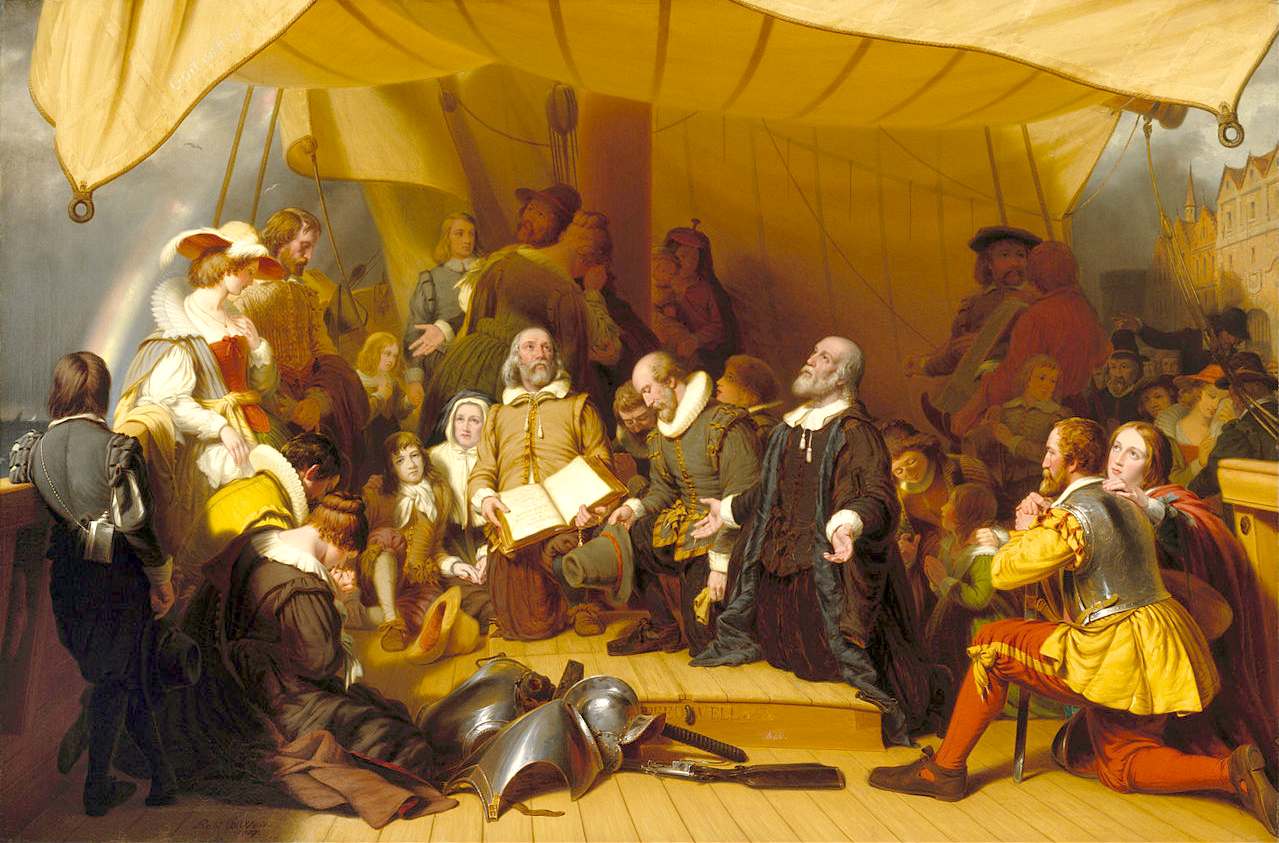

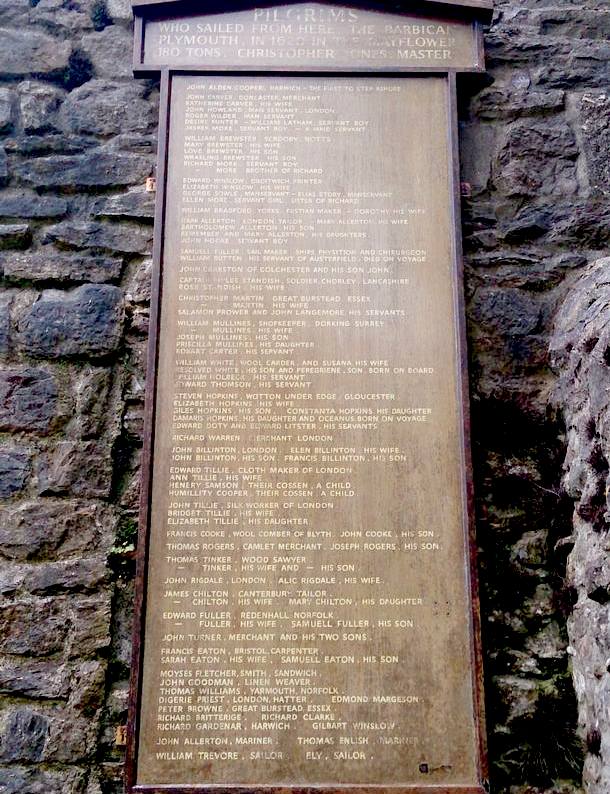

A brief contract was drafted to address this issue, later known as the Mayflower Compact, promising cooperation among the settlers "for the general good of the Colony unto which we promise all due submission and obedience." It organized them into what was called a "civill body politick," in which issues would be decided by voting, the key ingredient of democracy. It was ratified by majority rule, with 41 adult male Pilgrims signing for the 102 passengers (73 males and 29 females). Included in the company were 19 male servants and three female servants, along with some sailors and craftsmen hired for short-term service to the colony. At this time, John Carver was chosen as the colony's first governor. It was Carver who had chartered the Mayflower and his is the first signature on the Mayflower Compact, being the most respected and affluent member of the group. The Mayflower Compact is considered to be one of the seeds of American democracy and one source has called it the world's first written constitution.

The Mayflower compact is a significant historical document, the "wave-rocked cradle of our liberties", as one historian evocatively put it. Signed by the Pilgrims and the so-called Strangers, the craftsmen, merchants and indentured servants brought with them to establish a successful colony, it agreed to pass "just and equal laws for the good of the Colony". The first experiment in New World self-government, some scholars even see it as a kind of American Magna Carta, a template for the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution. Yet scholars at the Constitutional Center in Philadelphia suggest it had largely been forgotten by the time the Founding Fathers gathered at Independence Hall. Nor did the Pilgrims' belief in what Robert Hughes once called "the hierarchy of the virtuous" square with the more secular poetry of the Declaration of Independence that all men are created equal, and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights. Besides, the Mayflower compact started with a declaration of loyalty to King James.

The legacy of the pilgrims and the puritans is foundational. The work ethic. The fact Americans don't take much annual holiday. Notions of self-reliance and attitudes towards government welfare. Laws that prohibit young adults from drinking in bars until the age of 21. A certain prudishness. The religiosity. Americans continue to expect their presidents to be men of faith. In fact, no occupant of the White House has openly identified as an atheist. Also the profit motive was strong among the settlers, and with it the belief that prosperity was a divine reward for following God's path - a forerunner of the gospel of prosperity preached by modern-day television evangelists.

RELIGIOUS PERSECUTION

The Pilgrims were the English settlers who came to North America on the Mayflower and established the Plymouth Colony in what is today Plymouth, Massachusetts, named after the final departure port of Plymouth, Devon. Their leadership came from the religious congregations of Brownists, or Separatist Puritans, who had fled religious persecution in England for the tolerance of 17th-century Holland in the Netherlands.

They held many of the same Puritan Calvinist religious beliefs but, unlike most other Puritans, they maintained that their congregations should separate from the English state church, which led to them being labeled Separatists. After several years living in exile in Holland, they eventually determined to establish a new settlement in the New World and arranged with investors to fund them. They established Plymouth Colony in 1620, which became the second successful English settlement in North America, following the founding of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. The Pilgrims' story became a central theme in the history and culture of the United States.

THE VOYAGE

With personal and business matters agreed upon, the Pilgrims procured supplies and a small ship. Speedwell was to bring some passengers from the Netherlands to England, then on to America where it would be kept for the fishing business, with a crew hired for support services during the first year. The larger ship Mayflower was leased for transport and exploration services.

The Speedwell was originally named Swiftsure. It was built in 1577 at 60 tons and was part of the English fleet that defeated the Spanish Armada. It departed Delfshaven in July 1620 with the Leiden colonists, after a canal ride from Leyden of about seven hours. It reached Southampton, Hampshire, and met with the Mayflower and the additional colonists hired by the investors. With final arrangements made, the two vessels set out on August 5 (Old Style)/August 15 (New Style).

Soon after, the Speedwell crew reported that their ship was taking on water, so both were diverted to Dartmouth, Devon. The crew inspected Speedwell for leaks and sealed them, but their second attempt to depart got them only as far as Plymouth, Devon. The crew decided that Speedwell was untrustworthy, and her owners sold her; the ship's master and some of the crew transferred to the Mayflower for the trip. William Bradford observed that the Speedwell seemed "overmasted", thus putting a strain on the hull; and he attributed her leaking to crew members who had deliberately caused it, allowing them to abandon their year-long commitments. Passenger Robert Cushman wrote that the leaking was caused by a loose board.

Of the 120 combined passengers, 102 were chosen to travel on the Mayflower with the supplies consolidated. Of these, about half had come by way of Leiden, and about 28 of the adults were members of the congregation. The reduced party finally sailed successfully on September 6 (Old Style)/September 16 (New Style), 1620.

Initially the trip went smoothly, but under way they were met with strong winds and storms. One of these caused a main beam to crack, and the possibility was considered of turning back, even though they were more than halfway to their destination. However, they repaired the ship sufficiently to continue using a "great iron screw" brought along by the colonists (probably a jack to be used for either house construction or a cider press). Passenger John Howland was washed overboard in the storm but caught a top-sail halyard trailing in the water and was pulled back on board.

One crew member and one passenger died before they reached land. A child was born at sea and named Oceanus.

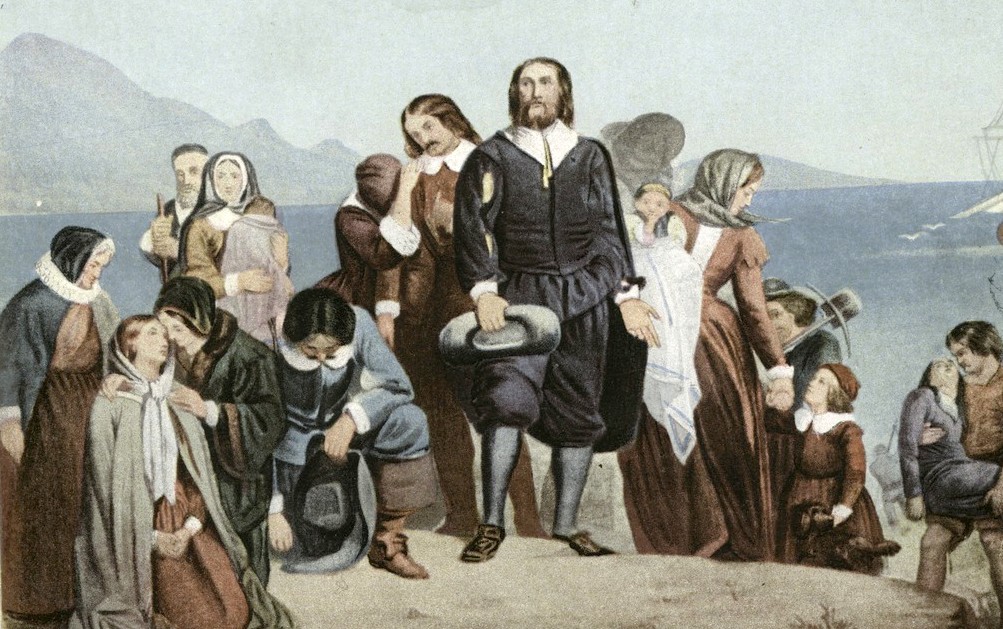

The Mayflower passengers sighted land on November 9, 1620 after enduring miserable conditions for about 65 days, and William Brewster led them in reading Psalm 100 as a prayer of thanksgiving. They confirmed that the area was Cape Cod within the New England territory recommended by Weston. They attempted to sail the ship around the cape towards the Hudson River, also within the New England grant area, but they encountered shoals and difficult currents around Cape Malabar (the old French name for Monomoy Island). They decided to turn around, and the ship was anchored in Provincetown Harbor by November

11.

MAYFLOWER

PILGRIMS VOYAGE - Pilgrimages take place all over the world, many

times each years, with migrants seeking to escape tyranny or persecution

in one form or another. The Founding Fathers were no different, but set

off at a time where opportunities abounded in relatively under-populated

countries, such as America and Australia, where the inhabitants did not

have strict border and immigration controls. It was a time of

opportunity for those with pioneering spirit, that even today, officials

try to kick out of you with financially enslaving taxing and laws, to

help them sustain their empires. At least we've stopped burning people

at the stake in town centres. Today, colonization is the dream of would

be interplanetary

travelers. But they are going to need more than a Space Shuttle

version of the Mayflower. Be careful when seeking to impress your views

on the free will of others. It can lead to civil war and the virtual annihilation

of indigenous peoples.

SETTING OUT

In early September, western gales turned the North Atlantic into a dangerous place to sail. The Mayflower's provisions were already quite low when departing Southampton, and they became lower still by delays of more than a month. The passengers had been on board the ship this entire time, feeling worn out and in no condition for a very taxing, lengthy Atlantic journey cooped up in the cramped spaces of a small ship.

When the Mayflower sailed from Plymouth alone on September 16, 1620, with what Bradford called "a prosperous wind", she carried 102 passengers plus a crew of 25 to 30 officers and men, bringing the total aboard to approximately 130. However, at about 180 tons, the Mayflower was considered a smaller cargo ship, having traveled mainly between England and Bordeaux with clothing and wine, not an ocean ship. Nor was it in good shape, as it was sold for scrap four years after her Atlantic voyage. She was a high built craft forward and aft measuring approximately 100 feet (30 m) in length and about 25 feet (7.6 m) at her widest point.

ACROSS THE NORTH ATLANTIC

The living quarters for the 102 passengers were cramped, with the living area about 80 feet by 20 feet (1,600 sq. feet,) and the ceiling about five feet high. With couples and children packed closely together for a trip lasting two months, a great deal of trust and confidence was required among everyone aboard.

John Carver, one of the leaders on the ship, often inspired the Pilgrims with a "sense of earthly grandeur and divine purpose." He was later called the "Moses of the Pilgrims," notes historian Jon Meacham. The Pilgrims "believed they had a covenant like the Jewish people of old," writes author Rebecca Fraser. "America was the new Promised Land." In a similar vein, early American writer James Russell Lowell stated, "Next to the fugitives whom Moses led out of Egypt, the little shipload of outcasts who landed at Plymouth are destined to influence the future of the world."

The first half of the voyage proceeded over calm seas and under pleasant skies. Then the weather changed, with continuous Northeasterly storms hurling themselves against the ship, and huge waves constantly crashing against the topside deck. In the midst of one storm, the servant of physician Samuel Fuller died and was buried at sea. A baby was also born, christened Oceanus Hopkins. During another storm, so fierce that the sails could not be used, the ship was forced to drift without hoisting its sails for days, or else risk losing her masts. The storm washed a male passenger, John Howland, overboard. He had sunk about 12 feet until a crew member threw out a rope, which Howland managed to grab, and he was safely pulled back on board.

The passengers were forced to crouch in semi-darkness below deck as ocean swells rose to over a hundred feet. With waves tossing the boat in different directions, men held onto their wives, who themselves held onto their children. Water was soaking everyone and everything above and below deck.

However, in mid-ocean, the ship came close to being totally disabled and may have had to return to England or risk sinking. A storm had so badly damaged its main beam that even the sailors despaired. By a stroke of luck, one of the colonists had a metal jackscrew that he had purchased in Holland to help in the construction of the new settler homes. They used it to secure the beam, which kept it from cracking further, thus maintaining the seaworthiness of the vessel. All told, despite the crowding, unsanitary conditions and sea sicknesses, there was only one fatality during the voyage.

The ship's cargo included many stores that supplied the Pilgrims with the essentials needed for their journey and future lives. It is assumed that they carried tools, food and weapons, as well as some live animals, including dogs, sheep, goats, and poultry. The ship also held two small 21-foot boats powered by oars or sails. There were also artillery pieces aboard, which they might need to defend themselves against enemy European forces or indigenous tribes.

THE

SHIP

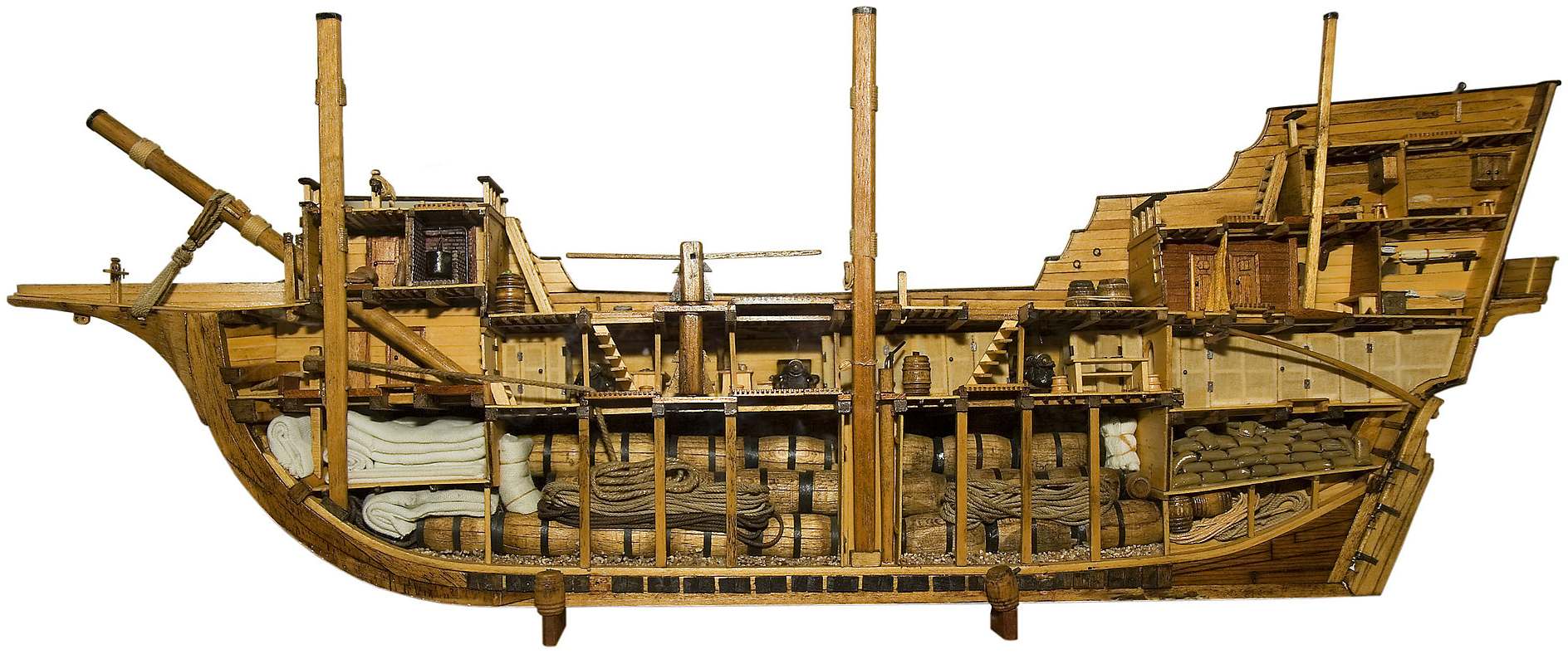

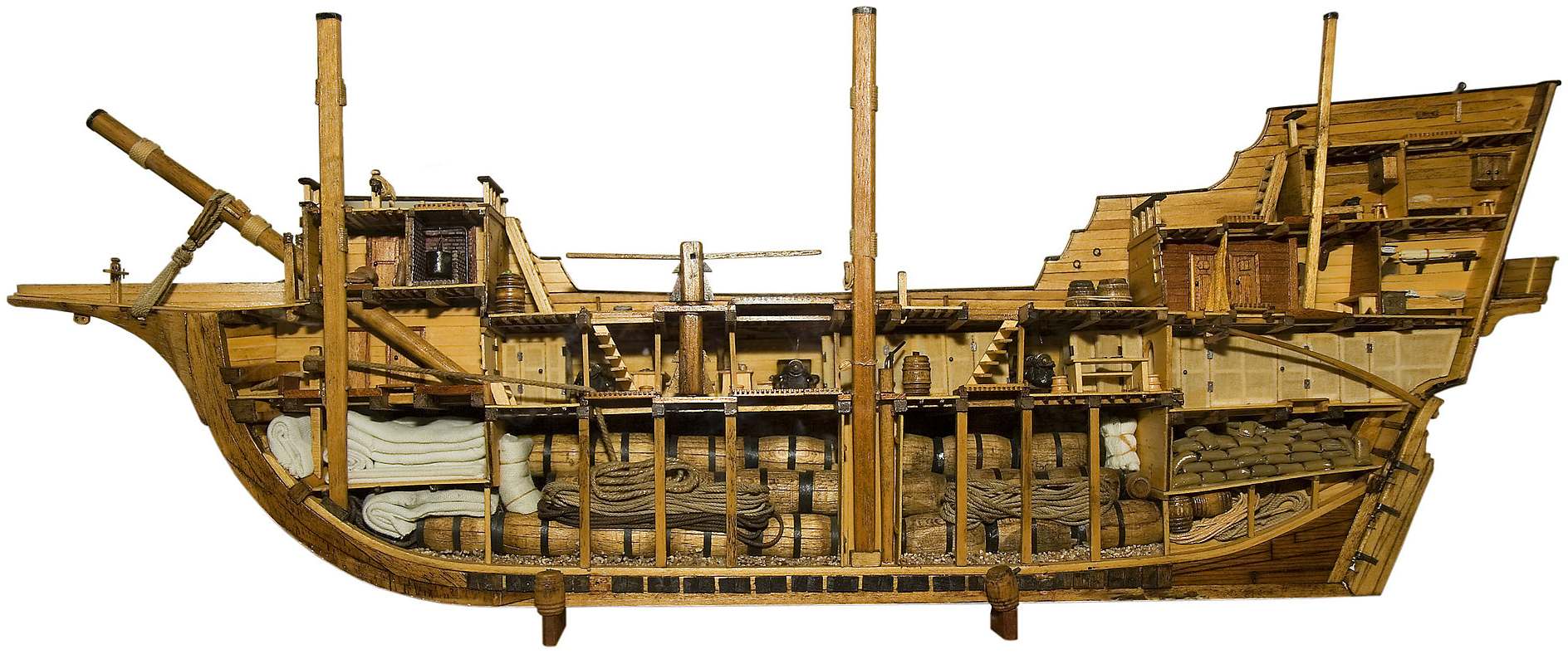

Mayflower was square-rigged with a beakhead bow and high, castle-like structures fore and aft which protected the crew and the main deck from the elements—designs that were typical of English merchant ships of the early 17th century. Her stern carried a 30-foot high, square aft-castle which made the ship difficult to sail close to the wind and not well suited against the North Atlantic's prevailing westerlies, especially in the fall and winter of 1620; the voyage from England to America took more than two months as a result. Mayflower's return trip to London in April–May 1621 took less than half that time, with the same strong winds now blowing in the direction of the voyage.

Mayflower's exact dimensions are not known, but she probably measured about 100 feet (30 m) from the beak of her prow to the tip of her stern superstructure, about 25 feet (7.6 m) at her widest point, and the bottom of her keel about 12 feet (3.6 m) below the waterline. William Bradford estimated that she had a cargo capacity of 180 tons, and surviving records indicate that she could carry 180 casks holding hundreds of gallons

each. The general layout of the ship was as follows:

Three masts: mizzen (aft), main (midship), and fore, and also a spritsail in the bow area

Three primary levels: main deck, gun deck, and cargo hold

Aft on the main deck in the stern was the cabin for Master Christopher Jones, measuring about ten by seven feet (3 m × 2.1 m). Forward of that was the steerage room, which probably housed berths for the ship's officers and contained the ship's compass and whipstaff (tiller extension) for sailing control. Forward of the steerage room was the capstan, a vertical axle used to pull in ropes or cables. Far forward on the main deck, just aft of the bow, was the forecastle space where the ship's cook prepared meals for the crew; it may also have been where the sailors slept.

The poop deck was located on the ship's highest level above the stern on the aft castle and above Master Jones' cabin. On this deck stood the poop house, which was ordinarily a chart room or a cabin for the master's mates on most merchant ships; but it might have been used by the passengers on Mayflower, either for sleeping or cargo.

The gun deck was where the passengers resided during the voyage, in a space measuring about 50 by 25 feet (15.2 m × 7.6 m) with a five-foot (1.5 m) ceiling. But it was a dangerous place if there was conflict, as it had gun ports from which cannon could be run out to fire on the enemy. The gun room was in the stern area of the deck, to which passengers had no access because it was the storage space for gunpowder and ammunition. The gun room might also house a pair of stern chasers, small cannon used to fire from the ship's stern. Forward on the gun deck in the bow area was a windlass, similar in function to the steerage capstan, which was used to raise and lower the ship's main anchor. There were no stairs for the passengers on the gun deck to go up through the gratings to the main deck, which they could reach only by climbing a wooden or rope ladder.

Below the gun deck was the cargo hold where the passengers kept most of their food stores and other supplies, including most of their clothing and bedding. It stored the passengers' personal weapons and military equipment, such as armor, muskets, gunpowder and shot, swords, and bandoliers. It also stored all the tools that the Pilgrims would need, as well as all the equipment and utensils needed to prepare meals in the New World. Some Pilgrims loaded trade goods on board, including Isaac Allerton, William Mullins, and possibly others; these also most likely were stored in the cargo hold. There was no privy on Mayflower; passengers and crew had to fend for themselves in that regard. Gun deck passengers most likely used a bucket as a chamber pot, fixed to the deck or bulkhead to keep it from being jostled at sea.

Mayflower was heavily armed; her largest gun was a minion cannon which was brass, weighed about 1,200 pounds (545 kg), and could shoot a 3.5 pound (1.6 kg) cannonball almost a mile (1,600 m). She also had a saker cannon of about 800 pounds (360 kg), and two base cannons that weighed about 200 pounds (90 kg) and shot a 3 to 5 ounce ball (85–140 g). She carried at least ten pieces of ordnance on the port and starboard sides of her gun deck: seven cannons for long-range purposes, and three smaller guns often fired from the stern at close quarters that were filled with musket balls. Ship's Master Jones unloaded four of the pieces to help fortify Plymouth Colony.

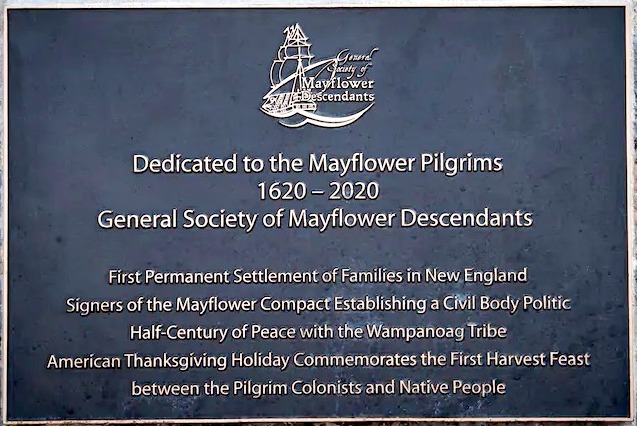

300TH ANNIVERSARY

The 300th Anniversary of Mayflower's Landing was commemorated in 1920 and early 1921 by celebrations throughout the United States and by countries in Europe. Delegations from England, Holland and Canada met in New York. The mayor of New York, John Francis Hylan, in his speech, said that the principles of the Pilgrim's Mayflower Compact were precursors to the United States Declaration of Independence. While American historian George Bancroft called it "the birth of constitutional liberty." Governor Calvin Coolidge similarly credited the forming of the Compact as an event of the greatest importance in American history:

It was the foundation of liberty based on law and order, and that tradition has been steadily upheld. They drew up a form of government which has been designated as the first real constitution of modern times. It was democratic, an acknowledgment of liberty under law and order and the giving to each person the right to participate in the government, while they promised to be obedient to the laws.

2020

MAYFLOWER

TRIMARAN - 1. The solar-powered research boat will aim to traverse the Atlantic Ocean

in 2021 with no humans on board. 2. Sea trials are due to commence off the south coast of England in

late 2020. 3. The Mayflower was officially unveiled on September 16th

2020, the 400th anniversary of the original Mayflower departure.

400TH

ANNIVERSARY 2020

The 400th Anniversary of Mayflower's Landing will take place in 2020. Organizations in the UK and US are preparing for celebrations to mark the voyage. Festivities celebrating the anniversary have already begun in various places in New England. Other celebrations are planned in England and the Netherlands, where the Pilgrims were living in exile until their voyage. However, the coronavirus pandemic has forced some plans to be put on hold.

Among some of the events planned are the Mayflower Autonomous Ship, without any persons aboard, which will use an AI captain designed by IBM

and Promare to self-navigate across the ocean. While the Harwich Mayflower Heritage Centre is hoping to build a replica of the ship at Harwich, England. Descendants of the Pilgrims are hoping for a "once-in-a-lifetime" experience to commemorate their ancestors.

PLYMOUTH HERALD 22 SEPTEMBER 2020

The dark and uncomfortable truth about the Mayflower Pilgrims

Meet the REAL Mayflower Pilgrims. They weren't from Plymouth, they may have eaten each other, and they landed in the wrong place.

Mayflower 2020, the 400th anniversary of The Mayflower setting sail from Plymouth, is fast approaching.

Myths, lies and races to lay claim to the Pilgrims are already hotting up.

But we've dug deep into the mythology and legend surrounding the Pilgrims and Plymouth's own link – or not, as history suggests – with the 'Founding Fathers'.

These are the real stories of the so-called Mayflower Pilgrims - and many of them are dark and uncomfotable.

In 2005 it was reported how archeologists from Taunton University carried out excavations on Cole's Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts which turned up the bones of several Pilgrims. What they found raised unsettling quesitons.

According to the website www.genealogue.com, the archeological team leader Stephen Holman examined some of the bones which bore "unususual markings".

He said: "It looked like something, or someone, had gnawed on them. The joints showed signs of deliberate butchering, perhaps with a hatchet."

Subsequent exhumations confirmed Mr Holman's suspicions.

The findings called into question the accepted history of the Pilgrim's first winter of 1620-21, including accounts written by the Pilgrims themselves. In none of these works was there any mention of cannibalism - a fact which was not exactly a surprise to anthropologist Mary Donner, also of Taunton University.

She said: "Cannibalism is not something the Pilgrims would have been proud of, and it's not something the company's investors would have been thrilled to hear about. It's entirely likely that the colonists swore an oath never to speak of it."

The remarkable discovery was given greater weight a few years later when the highly respected Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC announced in 2013 how historians and archeologists discovered a skull and a tibia of a teenage girl following excavations of a rubbish pit in James Fort.

They found unusual cuts on the bones consistent with butchering for meat. James Fort, founded in 1607, was the earliest part of the Jamestown colony which was one of the first permanent encampment made up of English settlers.

Evidence suggested the marks on the bones were "absolutely consistent with dismemberment and de-fleshing of this body".

Documents had previously suggested desperate colonists had resorted to cannibalism after a series of harsh winters. A particularly harsh winter of 1609 - 1610 was known to historians as the Starving Time.

The Starving Time was one of the most horrific periods of early colonial history. The James Fort settlers were under siege from the indigenous Indian population and had insufficient food to last the winter.

First they ate their horses, then dogs, cats, rats, mice and snakes. Some, to satisfy their cruel hunger, ate the leather of their shoes. As the weeks turned to months, nothing was spared to maintain life. How many of the growing numbers of dead were cannibalised is unknown. But it is almost certain the girl was not the only victim.

It is now accepted that The Mayflower – which was built to transport goods and supplies but not people – did not land in Plymouth first.

The ship landed at the tip of Cape Cod, now known as Provincetown. Ironically, Provincetown is now well known as a longtime haven for artists, lesbians and gay men. It also has a booming whale-watching industry.

The Mayflower Pilgrims had originally aimed to land at the mouth of the Hudson River, next to what became New York City.

However, the Pilgrims had been beaten back by bad weather. With an approaching winter and depleted supplies they chose to sail across Cape Cod Bay to Plymouth to settle.

According to oral tradition, Plymouth Rock was the site where William Bradford and other Pilgrims first set foot on land. It wasn't until 1741 - 121 years after the arrival of the Mayflower - that a 10-ton boulder in Plymouth Harbor was identified as the precise spot where Pilgrim feet first trod.

The claim was made by 94-year-old Thomas Faunce, a church elder who said his father, who arrived in Plymouth in 1623, and several of the original Mayflower passengers assured him the stone was the specific landing spot.

So, basically, one of America's iconic symbols which has long inspired weepy-eyed patriotism is based entirely on evidence no better than 'you know my mate Dave? Well his dad once said he saw Elvis working at the local fish and chip shop, so it must be true'.

Plymouth, Massachusetts was not named by the Mayflower passengers after Plymouth, Devon.

America's Plymouth – originally known as Plimouth – had been named after Devon's Plymouth years earlier by previous explorers.

It was pure coincidence the Mayflower left from Devon's Plymouth and landed in the American Plymouth. And much as it will pain organisers of Plymouth's Mayflower 2020 celebrations, The Mayflower ship only left from Devon's Plymouth because bad weather and other difficulties had stopped her leaving from Southampton and Dartmouth.

Devon's Plymouth was effectively just a convenient layby on the glorious motorway to a holiday-of-a-lifetime destination. Where you ended up eating your fellow holidaymakers or being killed by the tour guide and hotel staff.

The Mayflower was not solely transporting "Pilgrims" to the New World.

Around 40 of the passengers were "Separatists" – later known as the Pilgrims – who did not want to be part of the Church of England and had been living in exile in Holland for years before their journey. Many of them had originally come from Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire and Lincolnshire.

One of the Separatists was William Brewster. He had been inspired by the radical words of Richard Clifton, the rector of the nearby village of Babworth. It is believed that Brewster founded a Separatist church in his family home, the manor house at Scrooby.

The Scrooby congregation made their first attempt to escape to Holland via Boston in Lincolnshire. In the autumn of 1607, they travelled secretly to Scotia Creek near Boston, where they had charted a ship to smuggle them out of the country. But the captain betrayed them and they were held and tried at Boston’s Guildhall. After a month’s imprisonment, most were released.

Undeterred, the following year, the Scrooby Separatists travelled north to board a ship at Immingham. Again though, they were pursued. This time, the men escaped to Holland. However, the women and children were on a separate boat and were caught. They were freed eventually, and all were reunited in Amsterdam.

It is not true that the foodstuffs they took with them to America were called Scrooby Snacks.

Other passengers were secular colonists from the Home Counties and London area who were sympathetic to the Separatist cause, but not part of the core group of dissidents.

The remaining passengers were hired hands, labourers, soldiers, manservants and craftsmen needed for the crossing and the key first few months ashore. The Separatists called these people The Strangers. Which does rather sound like one of the colonies out of The Walking Dead.

The remaining 26 people on board were crew members.

The Separatists who founded the Plymouth Colony referred to themselves as "Saints," not "Pilgrims."

The use of the word "Pilgrim" to describe this group did not become common until the colony's bicentennial celebrations.

However, shortly after landing one of the settlers, Susannah White gave birth to a son aboard the Mayflower, the first English child born in New England. He was named Peregrine, derived from the Latin for ‘pilgrim’.

The Pilgrims were remarkably tolerant of other religious beliefs.

The Puritans, who settled the region north of Plymouth, were known for their strict approach to how religion was practiced within their borders.

However, the Pilgrims, never made any attempts to convert outsiders to their faith, including the Native Americans they met and the nonbelievers who joined them as labourers.

While they did not celebrate Christmas, they did not stop others taking the day off and celebrating it.

During March 1621, an English speaking Native American, named Samoset, entered the grounds of the Plymouth colony and introduced himself. He is said to have asked for a beer and spent the night talking with the settlers. Samoset, later, brought another Native American, Squanto, to meet the Pilgrims. Squanto’s English was more advanced. They arranged a meeting with the Wampanoag chief, Massasoit.

The relationship between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims developed. The Wampanoag taught the Pilgrims how to hunt and grow crops. They began trading furs with each other. Squanto lived with the Pilgrims, acting as an advisor and translator, ensuring their safe and prosperous relationships with other natives.

In the autumn of 1621, the colonists celebrated a successful and bountiful harvest in a three day festival of prayer with the

Wampanoag. This has become known as the first Thanksgiving.

Many of those who travelled aboard the Mayflower ended up in a mass grave in what is now known as Coles Hill, opposite Plymouth Rock.

Appearing a simple grass hill, it contains all the Pilgrims who died during the first winter.

It has no grave markers but a small monument at the top of the hill contains the remains of some Pilgrim bones that have eroded out of the hillside in previous storms.

About fifty of those who came in the Mayflower were buried on this spot, near the foot of Middle-street. Among them were Gov. Carver, William White, Rose Standish, the wife of Captain Standish; Elizabeth, the wife of Edward Winslow, Christopher Martin, William Mullins, John and Edward Tilley, Thomas Rogers, Mary, the wife of Isaac Allerton.

In a storm of 1735 a torrent pouring down Middle Street made a ravine in Cole’s Hill and washed many human remains down into the harbor.

Nearby is Burial Hill, which was Plymouth's cemetery from 1640 and contains a number of Mayflower passengers.

Many Pilgrim families were buried in the same general location within the cemetery.

During the voyage, manservant John Howland went on deck to escape the cramped conditions and was quickly swept into the sea. He grabbed ahold of a rope and hung on, in freezing waters, until he was eventually rescued.

He went on to live into his 90s, and fathered many children and grandchildren. His descendents include Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, Humphrey Bogart and

Alec

Baldwin.

Others who can trace their lineage back to Howland include Franklin Roosevelt and both George Bushes.

The Pilgrims had no authority to settle in Plymouth, only in the Hudson River area.

However, with no governing authority they decided to draw up their own "laws" to bind them into a civil society.

The Mayflower Compact is just one paragraph and begins "In the name of God. Amen."

While it did not set up any formal type of government or establish rules or elections, it did establish there would be a government and that all the signatories would abide by any laws made.

Some have argued that the Mayflower Compact was the first American document of Christian self-government. By Carl Eve

THE GUARDIAN 20 SEPTEMBER 2020

Pilgrim fathers: harsh truths amid the Mayflower myths of nationhood

As Plymouth marks 400 years since the colonists set sail, the high price paid by Native American tribes is now revealed in an exhibition

For a ship that would sail into the pages of history, the Mayflower was not important enough to be registered in the port book of Plymouth in 1620. Pages from September of that year bear no trace of the vessel, because it was only only 102 passengers and not cargo, making it of no official interest.

The port book is one of the many surprising objects at Mayflower 400: Legend & Legacy, the inaugural exhibition of the Box in Plymouth, Devon, which will open to the public later this month, and which is part of the city’s efforts to mark the 400th anniversary of the ship’s Atlantic crossing.

“This wasn’t a huge historic voyage in 1620. If anything, it was an act of madness because they were going at the wrong time of year into an incredibly dangerous Atlantic,” said the exhibition’s curator, Jo Loosemore.

The omission in the port book is one of many gaps surrounding the voyage of the Mayflower that the exhibition tries to fill. The general story is well known: the Mayflower took its 102 men, women, and children – the majority of whom were Puritan religious dissenters known as Separatists, but also called Pilgrims – from Plymouth to what they hoped would be the Hudson river. They endured a treacherous 66-day voyage and were blown off course, landing on the tip of what is now Massachusetts, before crossing the bay to set up a colony on land belonging to the Wampanoag, whose name means “people of the first light” and who had inhabited the area for some 12,000 years.

They had an estimated population of at least 15,000 in the early 1600s, and lived in villages on the Massachusetts coast and inland. Their help enabled the English to survive, and also became the basis for the much-mythologised first Thanksgiving feast, still celebrated in the US as a national holiday, though not without controversy. The reality, as this exhibition shows, was far more complicated – and violent.

Although the Pilgrims are often used as an origin myth for the US, the English were late arrivals to North America. Juan Ponce de León explored Florida as early as 1513, and the Spanish had a settlement in St Augustine by 1565, while French Huguenots tried and failed to establish a colony on the coast of what is now South Carolina in 1562.

Some 35 years before the Mayflower, two ships set sail from Plymouth to explore the North Carolina coast, and the following year the colony of Roanoke was established, but by 1590 all the settlers had disappeared. Eventually, in 1607, the English had success with the colony of Jamestown, Virginia, which managed to survive. As well as these early settlers, Europeans came to trade – and often to kidnap and enslave Native Americans – well before the arrival of the Pilgrims.

Part of the exhibition looks at these failed attempts at colonisation. “People living and working in Plymouth might be surprised about the importance that the city has played in that part of history,” said Nicola Moyle, head of heritage, art and film for the Box. “There were the Mayflower passengers, but more importantly the institutions that have roots in Plymouth that were playing a part in encouraging settlements taking place on the eastern part of the US.”

This was also the case for the Separatists. Although the mythology presents them as fierce critics of the Church of England seeking religious freedom, they had already found that in the Dutch city of Leiden, where they lived for a decade before crossing the Atlantic. What drove them onwards was the lack of economic opportunity.

“It’s just not the story we think it is,” said Loosemore. Economic factors fuelled the Separatists’ decision to obtain permission from the London Company of Virginia to establish a colony, and for funding from the Company of Merchant Adventurers.

But religious freedom and economic opportunity for the English would come at a heavy price for the Wampanoag. By the time the English arrived, the Wampanoag would have been familiar with Europeans, including the terrible diseases they brought. A few years before the Mayflower’s passengers landed, a plague wiped out an estimated 70% of their population. When the Pilgrims stepped ashore, the Wampanoag had been significantly weakened and were willing to make alliances with the English in order to keep their rivals, the Narragansett, at bay.

Although there were periods of good relations between the English and Wampanoag, there were also violent conflicts, culminating in King Philip’s War of 1675, which ended with the head of Metacom, the Wampanoag leader, being put on a spike and the survivors sold into slavery. It was a far cry from the scenes of a harvest celebration.

“These were people who came here for their religious freedom because they couldn’t worship as they pleased in their own country, and yet when they came to this country they did not seem to have that same tolerance for the people that they met here, despite all that the Wampanoag did to help them,” said Paula Peters, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Nation and of the advisory council to the exhibition. “You can’t have a colony without someone being colonised.”

The Wampanoag objects included in the show – some of which have never been seen outside the US – give a sense of both how they lived before the English arrived and after. One key piece is a commissioned pot by Wampanoag artist Ramona Peters, also known as Nosapocket, that draws from the group’s tradition. There is also a national touring exhibition of a new Wampum belt made of shell beads that will stop at the Box later this year.

Elsewhere in the exhibition is what is considered to be the first Bible printed in North America. Published in 1661, it is in the version of the Algonquian language that the Wampanoag spoke. It is known as the Eliot Indian Bible, named after chief evangelist John Eliot, who set up a series of “praying towns” to promote the conversion of the Native Americans to Christianity.

Yet the myth of Native American and English in Thanksgiving harmony remains, and these cheerful commemorations are the focus of the final part of the exhibition. There are display cases with Mayflower-related goods: plates and mugs, biscuit tins, stamps and tea towels. This mythology persists, despite the fact that the Pilgrims were not the first Europeans to arrive in North America, and their relationship with the Wampanoag was far from peaceful.

To Loosemore, the key to understanding this larger story lies in the rediscovery of a manuscript describing the Pilgrims’ experiences in the Netherlands and new world. Of Plymouth Plantation was written by the colony’s leader, William Bradford, 20 years after his arrival, but the manuscript was lost until 1855, when it surfaced in the collection of the bishop of London. “Its rediscovery has a lot to answer for in the sense that it inspired this Victorian interest in the Mayflower,” said Loosemore.

Around the same time, in the US, President Abraham Lincoln declared a Thanksgiving holiday in 1863 in an attempt at national unity while the civil war was under way. In the decades that followed, these strands merged together into a narrative, which was fostered by a New England elite that including many prominent US leaders who were Mayflower descendants, such as the second president, John Adams, whose letters are on display in the show.

Jamestown, with its slavery, and St Augustine, with its Spanish Catholics, were ignored, and the national story became that of the hard-working, freedom-seeking Protestant “Pilgrim fathers”, aided by kind Native Americans. Now, says Peters, there is a chance for the public to learn a different story.

“For me, it’s an opportunity to say, yes, we are still here, and what happened to us mattered.”

By Carrie Gibson

LINKS

& CONTACTS

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-54199565

https://www.plymouthherald.co.uk/news/history/mayflower-pilgrims-plymouth-link-myths-2026547

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/sep/20/pilgrim-fathers-harsh-truths-amid-the-mayflower-myths-of-nationhood

https://www.mayflower400uk.org/education/the-mayflower-story/

https://www.plimoth.org/learn/just-kids/homework-help/mayflower-and-mayflower-compact

http://mayflowerhistory.com/voyage